Chinese-American Civil Rights Fighter

“American Heathen” --The Stanford Graphic Novel Project

by Winny Lin

Vice President of CA South Bay Chapter

Out of the blue, I received an email about the publication

of a graphic novel project about Wong Chin Foo,王清福, the very first Chinese-American

activist, and his journey. Thanks

to both Shimon Tanaka and Scott Hutchins, Stanford lecturers and project

leaders, I received a copy and started reading.

The novel tells the story of a Chinese-American who in the

19th century pioneered the struggle for the civil rights of his own

people while under the restrictions of the Exclusion Act. Today, the scenery has changed. Chinese-Americans are working in every

field, no longer are they isolated in restaurants and laundries. Nevertheless, we are still struggling

to improve our rights and places in the United States of America.

It was amazing how Wong knew to use the same tactics we are

using today to fight for the rights for Chinese-Americans--- newspaper, associations,

testimony in US Congress, and traveling lectures.

In 1874 Wong became a naturalized US citizen. However when he exercised his right to

vote, he was thrown into jail. In

the novel he is quoted as saying “Cutting my queue, speaking perfect English,

lecturing to thousands---none of it matters.” It is still true that in parts of

America today, there is still subtle discrimination against Chinese-Americans.

I remember when our attorney first jokingly called my husband, “Chinaman” many

years ago, my smile froze and did not know how to respond. Last year when I

subbed in a 5th grade classroom in Kentucky, a girl was mocking me

and my accent. Where did all these come from? History and stereotype!?

The novel goes on to explain that Wong founded a weekly newspaper,

The Chinese American, in New York City for distribution east of the Rockies. The purpose was to keep the people

informed and organized to fight for their rights. In 1893, he wrote in his

paper about the Geary Act which extended the Exclusion Act and made it even

more onerous. The new law required

all Chinese to carry their resident permit, or they would be deported or get a

year of hard labor. As difficult

as it is to imagine, Chinese were not allowed to bear witness in court.

Wong established the Chinese

Rights League and organized meetings to discuss how to protest the hideous

Geary Act. “We won’t let stand a law that treats us like branded cattle” he is

quoted as saying. Over a thousand

prominent Americans came to

support his rally at Cooper Union in New York City. This reminded me of the rally held in Washington DC in 1963. I was not surprised to see in the novel

that Wong is compared to Martin Luther King, Jr. However, Wong used the same strategy way before King. Interesting!

The novel reports that he spoke for 150,000 Chinese in the

US and testified at Congressional hearings. He faced Congressman Thomas J. Geary himself and said “I

will not be photographed against my will like a criminal. I would be hanged first.” Why should Chinese be singled out for

this treatment? Although Wong did

not completely succeed, Secretary of the Treasury Carlisle did make modifications

to the government’s enforcement procedures under the Geary Act. So his effort did pay off!

Wong traveled the globe giving speeches to the American

public and promoted the awareness of Chinese culture, Confucianism, and the

evil of opium brought by western world to China. He even defended Chinese food against the rumor of rats and

cats served in Chinese restaurants. One time he offered $500 reward for anyone

who could prove that Chinese ate cats and rats. It is so sad that people in the Mid-West still asked me if

our Chinese restaurants in town serve cats and rats! History and stereotype! It

has not changed yet.

Other than his fight for civil rights, Wong struggled with

his own identity. Was he a Chinese

or an American? Once he was educated by Christian missionary and baptized into the Baptist faith.

However, when he spoke to the general American public, he often praised

Confucius’ teaching as the reason for a harmonious society and criticized “the

hypocrisy of Christianity”.

And that is “why I am a heathen”, he proclaimed. He worked hard to protect the rights of

Chinese in America, but was often sought after by Chinese tongs (secret societies

often engaged in illicit activities), because he wrote about the vices existing

in of Chinatowns.

When he was in China, the Qing

government put a reward on his head, due to his anti-government

activities. So where could he find

his place? Over 150 years later,

many of us also are facing the dilemma: Chinese or Americans? Or do we get the best of two worlds?

Before reading

this graphic novel, “American Heathen”, I was not aware of Wong Chin Foo (王清福) and his Chinese-American activism. USCPFA South Bay chapter recently had

several speakers to speak on the topics of Chinese-American’s history:

1.

Sweet and Sour: Life in Chinese Family

Restaurants by author John Jung and artist Flo Wong

2.

The Angel Island Story by Buck Gee, president of

the Board of Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation

3.

Long Overdue Dedication to Fishing Village by

activist and historian Gerry Low-Sabado.

I have found these very interesting and relevant, since I

immigrated to the USA during the influx of college graduates from Taiwan in the

70’s. This publication of

“American Heathen”, a project of a group of twelve students at Stanford has

added more depth of my understanding of the struggle of Chinese-Americans. Since the project leader, Shimon Tanaka came on October 25 and explained the process how the book was done, I feel more appreciative of this graphic novel, especially each of us present was gifted a signed copy. Thank you, Shimon. 謝謝!

photo #1 Many of us asked Shimon to sign our copy of the book.

photo #2 On behalf of the chapter, I presented Shimon with a certificate of appreciation.

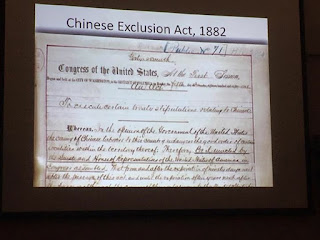

photo #3 Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

photo #1 Many of us asked Shimon to sign our copy of the book.

photo #2 On behalf of the chapter, I presented Shimon with a certificate of appreciation.

photo #3 Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.